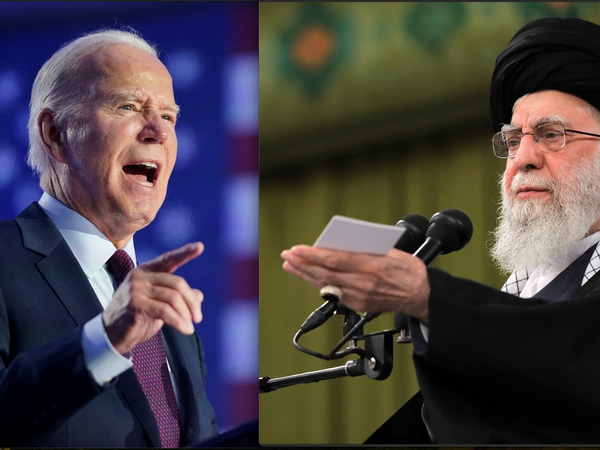

Since assuming the position of Supreme Leader of Iran in 1989, Ali Khamenei has steadfastly adhered to his ‘no-talks, no-détente’ policy towards the US, a pivotal element of his strategic approach.

This does not mean that the Iranian government refrained from clandestine and overt sporadic negotiations with the United States, undertaken with specific objectives to safeguard its interests. However, none of these negotiations were directed at alleviating tensions.

An illustrative instance and what ensued is evident in Khamenei's remarks during the 2015 nuclear talks: “The ongoing discussions, including those with Americans, solely revolve around the nuclear issue. Now, should the opposing side rectify its misconduct, that could serve as a precedent for broader discussions on other matters as well.”

However, subsequent developments revealed that this statement was not entirely candid. Consider the following timeline:

- The nuclear agreement between Iran and the world powers was concluded on July 14, 2015.

- The adoption date, i.e., the formal acceptance of the deal by Iran and the world powers, was set for October 18, 2015.

- Notably, on October 7, 11 days before the formalization of the agreement, Khamenei stated, “Talks with the US are prohibited because of the countless losses it incurs and the negligible benefits it offers.”

In essence, Khamenei expressed this view before even the ink on the signatures had dried, let alone allowing time to observe whether the US would rectify what he labeled as its ‘misconduct.’ When Donald Trump withdrew from the nuclear deal in 2018, it provided Khamenei with a golden opportunity to assert, “I told you so.” He said, “The nuclear talks were a mistake. I made a mistake. As a result of the insistence of the gentlemen (referring to the then moderate administration of Hassan Rouhani), I allowed an experiment.”

He has consistently asserted that the conflict between the Iranian government and the US is a “certain and inevitable” situation. The central doctrine of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards (IRGC), which is Iran’s other locus of power besides Khamenei, also maintains that the hostility between the Islamic Republic and America is “fundamental and existential that cannot be resolved through negotiation and compromise.”

But why is the Iranian radical camp led by Khamenei so resolute and persistent in maintaining its “no talks, no détente” stance towards the United States?

While a prevailing explanation attributes this unwavering position to ideological differences, and there is no denying of the role of ideology, over the course of Khamenei’s 35-year rule, three presidents—Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Mohammad Khatami, and Hassan Rouhani—attempted to mend US-Iran relations, all in vain.

Rafsanjani, who was the key to Khamenei becoming Supreme Leader, died in suspicious circumstances in 2017, while having been ostracized from politics. The other two presidents considered old guards, have not only been marginalized but also silenced. In a notable example, in 2003, under Khatami’s presidency, his administration unofficially proposed a “grand bargain deal” to the US government aimed at resolving all the disputed issues. The offer was rejected by the George W. Bush administration, which deemed it insincere without Khamenei's endorsement.

In contrast, the Soviet Union, despite deep ideological differences and strategic rivalry with the US during the peak of the Cold War, maintained diplomatic relations at the highest level and signed détente agreements with America. Similarly, communist-ruled China and Vietnam not only have full diplomatic relations with the US but also boast extensive economic ties.

A deeper comprehension of this conflict can be grasped through the lens of realpolitik. Khamenei censures individuals who advocate for negotiations with the US, remarking, "Some people are negligent and naive regarding talks [with the US] and fail to grasp the complexity of the issues." So, what exactly is the complexity of these issues?

Infiltration

Observing Khamenei's representatives across various institutions—ranging from the judiciary to the Guardian Council, the IRGC, the army, universities, and government agencies—it becomes apparent that Iran’s ruler staunchly supports individuals who harbor a shared sentiment of anti-Americanism and fears regarding the “infiltration” of America in Iran. In essence, by adhering to this stance, they are safeguarding their very existence.

The conservatives and Khamenei express deep concerns about the prospect of engaging in negotiations with the US and the potential relaxation of tensions, fearing the threat of "infiltration" that could jeopardize the existing traditionalist system. Within this apprehension, Khamenei underscores the significance of cultural influence as the most alarming form of infiltration. He asserts, “The enemy seeks to alter the societal beliefs in the cultural context, manipulating the very beliefs that have upheld this society (read the Islamic government) to inflict damage, create disruptions, and introduce breaches. They allocate billions of dollars for this purpose—this is cultural infiltration.”

Opening doors to America, given the significant allure of American pop culture, acknowledged as a key element of America’s soft power by the renowned political scientist Joseph Nye, could undermine the ideological foundation and authoritarian control of the system. While some argue that a considerable portion of society is already an admirer of Western culture, Khamenei’s concern pertains to the other segment—the traditionalists and devout religious individuals who, despite being a minority in Iran, currently support him, constituting the political base of the existing system.

Rise of technocrats

The rise of technocrats, a trend disliked by Khamenei and reminiscent of his predecessor, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who also distrusted them for their association with modernity and Western culture, could emerge as another consequence of nurturing economic ties with the US.

Reestablishing relations with the US could lead to an expansion of trade and commerce, consequently resulting in a surge in the number of Iranians visiting the US and vice versa. The consequence of such exchanges might manifest in the emergence of what conservatives call as “Westoxificated” technocrats as a significant force in Iranian society.

Reconciliation with the US - end of the revolution

Reconciliation with the United States would symbolize the demise of the revolution. Its conclusion would render the supreme leader, Revolutionary Guards, and the hard-line camp obsolete. This is why the IRGC emphasizes that the conflict between the US and Iran is existential and cannot be resolved through negotiations. Enmity towards the US serves as a rallying point for radicals and conservatives led by Khamenei to mobilize their supporters. Reconciliation with the US would undercut the narrative of the deep state, diminishing its capacity to rally its political and religious base, and repression of dissidents.

Where does this conundrum lead?

Khamenei and his cadre of hardliners blame Donald Trump for withdrawing from the nuclear deal. However, the reality is that Khamenei has undermined US-Iran relations for the last 35 years by obstructing sustained talks aimed at détente between the two states. In the absence of diplomacy and bilateral talks to alleviate and contain tensions both in rhetoric and actions—it was inevitable that, regardless of who occupied the White House in the years following the 2015 deal, the nuclear agreement would become unstable and collapse.

However, this is not the sole outcome of the current status quo crafted by Khamenei. When two governments are entrenched in such an antagonistic relationship, ceaselessly plotting and executing actions to harm each other's interests, and fail to mitigate tensions through talks, the question arises: what eventual solution remains other than war to resolve this conflict? Even if neither side expresses a desire for war, as both sides often assert, a spark or a miscalculation can ignite the flames of war. It is a matter of time.